The work of Vanessa Beecroft may look familiar to many due to her artistic collaboration with Kanye West. Working on the runway performances of the Yeezy fashion line and the music video for ‘Runaway’ Beecroft and Kanye West have created many striking and memorable pieces together. However, long before Beecroft’s involvement with Kanye West, she has been promoting her own brand and unique style of performance. Beecroft's primary method of artistic practice involves large scale projects which frequently include female models who are more often than not presented in the nude or wearing barely-there items of clothing or lingerie. Her work has provoked many reactions from members of the art world and spectators. Beecroft’s practice is regarded by some as sexist and degrading, while on the other end of the spectrum, her work is loved as revolutionary and thought provoking.

adidas Originals x Kanye West YEEZY SEASON 1 © Photo by Gareth Cattermole/Getty Images for adidas

The titles of Vanessa Beecroft's art pieces promote the very specific brand of the artist, and while also documenting the number of performances she has completed. Beecroft's art often stands to embody the contemporary geographical or social circumstance. The works are conceptualized with a specific site in mind, resulting in the performances being ephemeral and distinct in their location. However, Vanessa Beecroft has seen huge support from galleries and institutions who might not otherwise be as willing to support performance art. Beecroft's 'performances' are intensely documented through video and extensive photographs in order to preserve and publish this otherwise transitory experience. The photographs act as an enticement for the institutions, creating subsequent exhibitions and sales of the expensive souvenirs.

In 2001, Vanessa Beecroft began to work on her performance piece VB46 which was to take place at the Gagosian Gallery in Beverly Hills. Like many other of her performance works, Beecroft sought out a group of around 30 young women, with a very specific physical appearance. The advertisement for the position was posted in various locations throughout Los Angeles, reading

“Needed: 20–30 nude models, eighteen plus, skinny, tall androgynous body, very small breasts, available to pose nude. Preferably with short hair, boyish cut, blond, and fair. Will be covered in body makeup. Will wear Manolo Blahnik shoes.”

The specificity of Beecroft's practice extended not only to the types of bodies that she needed for VB 46 but also to the models behavior during the art piece. Beecroft's instruction to the models leaves very little room for activity or deviation from their stoic presence within the Gagosian. The instruction states;

"Do not talk, do not interact with others, do not whisper, do not laugh, do not move theatrically, do not move too quickly, do not move too slowly, be simple, be detached, be classic, be unapproachable, be tall, be strong, do not be sexy, do not be rigid, do not be casual, assume the state of mind that you prefer (calm, strong, neutral, indifferent, proud, polite, superior), behave as if you were dressed, behave as if no one were in the room, you are like an image, do not establish contact with the outside ." —Vanessa Beecroft"

The statement gives an insight into the so called live performance conducted by the artist and her team. Many critics and theorists view her performance pieces as 'Live Paintings', by which the subject matter we would usually only be confronted with in a painting, the classic female nude, is presented to the viewer in a gallery setting and also the way in which the works are composed. The spectator is confronted with the real body of the female nude, in its frankness, a situation which may cause a sense of discomfort to those used to seeing it on a canvas or a screen. However, aside from the model's actual real life presence, the instruction given to the models highlights how very little of Beecroft's performance can be understood as "live".

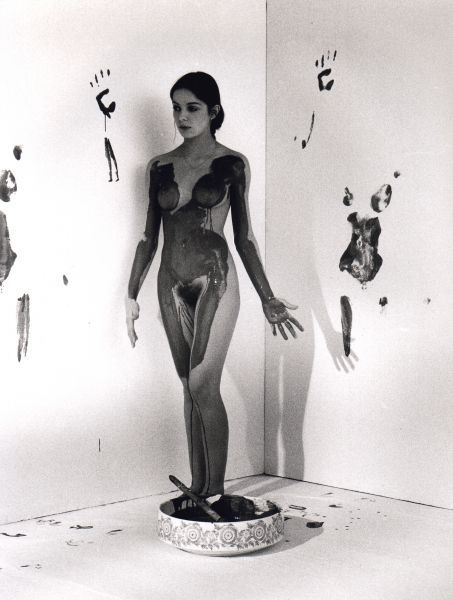

Yves Klein – Anthropometry Performance, 1960.

Beecroft's practice draws some interesting similarities and differences with Yves Klein, an artist who also attracted controversy through his artistic practice. Both artists distance themselves their chosen medium; the female body by presenting it as the primary focus of their artworks and using the body as a tool rather than treating participants as individuals. In contrast to Klein's models painting themselves, Beecroft's are designed by a team of make up artists; a feature which can be read as symptomatic of modern culture and the fashion world. Although both artist's rely on an index to document their work, Klein utilizes the painted print of the female body, while Beecroft relies on modern technology to record an ephemeral performance.

As previously mentioned, Vanessa Beecroft's practice is often reflective of the social or geographical position in which they take place. VB46 was Beecroft's first performance in Los Angeles, and therefore can be interpreted as a commentary on the work's location. Issuing a performance in Beverly Hills, VB46 may be read as a response to the City of Angels, with whitewashed beautiful figures posing in a white gallery which may be viewed as a form of contemporary heaven in an artistic realm. The models bleached appearance may signify a number of things, the sun of California, the interest in the speculation of whiteness, the purity of the female nude body, but it may also represent the mass infiltration of aspiring actresses, models and entertainers hoping to make their break in LA. By extracting these young hopefuls from the casting couch or auditions and placing them against the backdrop of a contemporary art gallery space, Beecroft highlights the strangeness of the uniformity and blatant objectification of women in the entertainment and fashion industries. Jennifer Doyle argues that 'Beecroft's installations are deliberately provocative- ‘clusters of naked and nearly naked skeletal women stare vacantly in space and mime the posture of haute couture, citing the conceptual runway antics of the season's hottest designers’.(1) Beecroft's practice holds many strong links to commodification and the commercial, both visually and theoretically.

Vanessa Beecroft, VB46 at the Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles, 2011. © Gagosian Gallery

The problem with Beecroft's insistency on the models remaining 'like an image', is that it perpetuates the image of the female body, in this case nude, as passive, objectified and arguably 'for sale'. Steinmetz, Cassils and Leary note that 'The process of production, selection, and manipulation in Beecroft's photographs serve to uphold dominant ideologies in the interest of brokering high-end luxury commodities.' (2) The models are lined up as if on a factory production line, with almost identical appearances, presented as commodities of Beecroft's project. VB46, among many of her other projects allows for the audience to behold a full scopophilic and fetishistic view on the passive, purified female nude. Beecroft herself notes in regards to VB46 'I recognize that the more I try to make the image minimal and pure the more fetishistic it looks.'(3) However, this reading of Beecroft's practice by many critics may also point to a problematic social issue rather than the artist's work itself. The constant objectification and sexualisation stands as a negative reflection of our own societal views and values, rather than the artist's display of these women.

As we have seen, there is a redemptive positive and even feminist reading applicable to VB46, as Jennifer Doyle notes that, 'On its face, Beecroft's work seems to forward a feminist critique of the art world by literalizing the place of women as objects of consumption/contemplation.' (4) However, upon deeper investigation and behind the scenes, Beecroft's practice tells a very different and unsettling story. Doyle further notes that her work 'adopts the pose of a critique of the objectification of women in art, but the power of that critique is all but completely dismantled by the institution that mounts it. (5)

As we know, There is a strong tradition of expressing feminist concerns in performance art, with artists such as Carolee Schneeman, Yoko Ono and Valie Export, among others, utilizing the female body in their performance to highlight or express gender inequality and a range of problems surrounding the female body in society. Their work offers a poignant expression of female issues through use of the artist’s body as subject matter. However by explicitly using other's bodies instead of the artist's own, does Vanessa Beecroft in fact become a part of the problem critics praise her for highlighting? The shift that occurs in this change of subject representation has huge effects on the negative perception of her work. Steinmetz, Cassils and Leary argue that 'Beecroft places the bodies of other women in positions potentially exploitative and demeaning rather than using her own body as a ground for experimentation.' (6)

The advertisement for a seemingly Aryan type models caught the attention of then students of California Institute of Arts students and feminist activist group Toxic Titties. Heather Cassils and Clover Leary, who fit the physical description, applied for the position, and were subsequently two of Beecroft’s first picks for the performance. Although many critics view Beecroft's performance pieces as a critique of the fashion industry, there is a troubling truth that stands behind the artworks.The disparity between Beecroft's precise and aesthetic final pieces and the process which occurs behind the scenes is startlingly described by Cassils and Leary in 'Behind Enemy Lines: Toxic Titties Infiltrate Vanessa Beecroft' also written with Julia Steinmetz. Both recall how each model was subject to hair bleaching and full bodily hair removal, the full extent of which was only revealed at the waxing salon by the apologetic beautician. As well as a complete makeover of the models physical appearance, they were givens strict instructions on how to behave during the show. Cassils and Leary also describe how Beecroft's presence was often mediated by another member of her team. 'Beecroft would whisper instructions into the ear of a male production manager, who would then relay instructions to the models, putting herself in the position of male authority and power only.' (7)

It is perhaps Beecroft's attempt to represent an esthetically striking artwork, which dismisses the pain of the process that makes her work so disturbing. In contrast to an artist like Santiago Sierra, who openly exploits the participants in his artworks such as 160cm Line Tattooed on 4 people el gallo arte contemporaneo. Salamanca December 2000, Beecroft's practice is shrouded in secrecy and even guilt. In a conversation with Heather Cassils, Beecroft stated that,' I have never come in contact with the models before.. It makes me feel guilty. (8) The stoic, futurist and even alien representation of the female body is one which offers a stark look on the use of the woman's body in mass media, art and more generally as a commodity. Yet Leary and Cassil's description of their treatment and anxieties during the duration of their time "working" under Beecroft illustrates the extreme, almost torturous lengths the artist and her team are willing to impose on models to produce a visually striking piece of art. Doyle perfectly articulates this tension, stating that Beecroft's work 'finalizes the marriage of art and fashion, and renders visible the libidinal dynamics of art consumption: gorgeous bodies served up to paying customers under the guise of aesthetic contemplation and enjoyment.' (9)

In conclusion, Beecroft's VB46 as well as her other artworks hold subjective and very diverse meanings. Beecroft herself gives very little of her intended meaning or political agenda away to viewers. Lucy Soutter's description of female artists working with narrative photography in the 1990s called Panty Photographers, is also very apt in describing Beecroft's practice. Soutter states 'As far as I can tell, panty photographer's like to keep their politics as ambiguous as their imagery; the potential that their stance might actually be masochistic, misogynistic, or crassly materialistic is another optional overlay, to be retained or discarded by the viewer at whim.' (10) The ambiguity of Beecroft's intended message allows for both positive and negative interpretations to her work, with undeniable controversy.

Vanessa Beecroft, VB46 at the Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles, 2011. © Dusan Reljin

1. Jennifer Doyle, 'White Sex: Vaginal Davis does Vanessa Beecroft', Sex Objects: Art and the Dialectics of Desire, (Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 122.

2.Julia Steinmetz, Heather Cassils and Clover Leary, 'Behind Enemy Lines: Toxic Titties Infiltrate Vanessa Beecroft'. in Signs, 31:3, New Feminist Theories of Visual Culture (Spring 2006), 777.

3. Marcella Beccaria, Vanessa Beecroft: Performances 1993-2003, (Milan: Skira; London: Thames and Hudson,2003), 325.

4. Doyle, 'White Sex', 129.

5. Ibid, 132.

6. Steinmetz, Cassils and Leary, 'Behind Enemy Lines', 765.

7. Ibid, 760.

8. Heather Cassils, 'Conversation during a break between photo and video shoots at the Sony sound Stage, Culver City, CA., October 2003', (ibid), 760.

9. Doyle,' White Sex', 122.

10. Lucy Soutter, 'Dial ‘P’ for Panties: Narrative Photography in the 1990s.', Afterimage, (vol. 27, no. 4, January/February 2000), 12.